Phase one of the BSO’s two-year Beethoven/Schoenberg project continues next week with three performances of Gurrelieder , Schoenberg’s three-part cantata/song cycle/symphony, led by James Levine. The text, by the Danish poet Jens Peter Jacobsen, tells of the doomed love of King Waldemar and the beautiful Tove. Despite the mythical story and the firmly tonal late-romantic sound picture, Gurrelieder has always had an ominous aura.

Phase one of the BSO’s two-year Beethoven/Schoenberg project continues next week with three performances of Gurrelieder , Schoenberg’s three-part cantata/song cycle/symphony, led by James Levine. The text, by the Danish poet Jens Peter Jacobsen, tells of the doomed love of King Waldemar and the beautiful Tove. Despite the mythical story and the firmly tonal late-romantic sound picture, Gurrelieder has always had an ominous aura.

You can get a sense of that aura just by thumbing through the score. The music seems forbiddingly dense on paper — lines of music cover every inch of the oversized page, barely a pica of space between them. When Schoenberg wrote the piece (mostly in 1900), the forces it called for were unprecedented: an orchestra of 150, a huge mixed chorus and separate male choir, and six vocal soloists, including a speaker.

The number of musicians — generally between 450 and 500 — adds to that sense of immensity. Virtually every synonym for “big” has attached itself to Gurrelieder over the years: “huge,” “mammoth,” “vast,” “gigantic,” “epic,” “gargantuan,” and whatever else the thesaurus can suggest. Only Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, written a few years later, would rival it. The last thing, it seems, you would want on your iPod.

Yet for all its square footage, Gurrelieder is an intimate piece. In the notes to his 2002 recording, Simon Rattle calls it “the world’s largest string quartet.” He’s on to something: look at that score again and you discover that there are few places where all or even most of the musicians play together. And what’s remarkable is the delicacy and transparency with which Schoenberg handles the instrumentation in his first orchestral work. This chamber-music aspect may explain why, for such an allegedly thorny piece, there are so many excellent recordings in the catalogue: Chailly, Abbado, Boulez, Ozawa, Rattle, and Levine himself, from his Munich days.

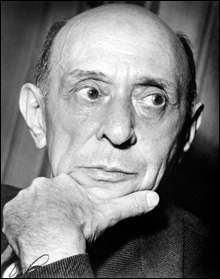

Schoenberg called Gurrelieder “the key to my development.” Largely complete in piano score by 1901, it wouldn’t be heard in its entirety until 1913. The task of orchestrating Part III would consume him, on and off, for 10 years. That decade saw the first radical change in Schoenberg’s musical language: the famous “liberation of the dissonance.” As Allen Shawn points out in his invaluable Arnold Schoenberg’s Journey , the effect of that change is audible in the third part, whose sound picture — more skittish and less lush — bears a marked resemblance to the atonal works Schoenberg was writing at the time.

By the time of its premiere, on February 23, those works had made the composer a cultural flashpoint, subject of broadsides in the press and instigator of fistfights in the audience. The debut of Gurrelieder was one of very few unalloyed triumphs of Schoenberg’s career: the ovation lasted half an hour and many in the audience wept. But the key had been turned, and the composer had already left its syntax behind on his lonely journey into the future.

James Levine conducts the BSO in Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder, with soloists Karita Mattila, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, John Botha, Paul Groves, Albert Dohmen, and Waldemar Kmentt and the Tanglewood Festival Chorus | Symphony Hall, 301 Mass Ave, Boston | February 23-25 @ 8 pm | $28-$108 | 617.266.1200 or www.bso.org | To be repeated at Tanglewood on July 14 with a slightly different cast