FORMAL RHYTHMS Purity and calm seemed the aim of Erik Satie's Socrate — and of Mark Morris's

Socrates. |

Erik Satie called his vocal work Socrate a "symphonic drama," though it's anything but dramatic in a theatrical sense — or symphonic, either. Based on excerpts from the dialogues of Plato, the text describes the philosopher's influence, his friendships, and his suicide in prison. Completed in 1920, the music aimed for purity and calm, as an antidote, perhaps, to the horrors of the Great War that had just ended. Socrate was originally scored for orchestra and four sopranos, but Satie made an even more transparent version for solo voice and piano. It's this arrangement that Mark Morris and Celebrity Series brought to the Cutler Majestic last weekend.

Socrates is Morris at his most austere. Without even minimally identified characters, this is a work for the ensemble. Fifteen dancers do almost nothing but walk, as tenor Michael Kelly sings the text, in French, accompanied by pianist Colin Fowler. The dance illustrates the words, probably more one-on-one than I could detect, though I'd read an English translation in the program beforehand. I decided that Morris was adding a layer of displacement onto a story that had already been several times removed — from Plato's account, through Victor Cousin's Greek-to-French translation, to Satie's musical setting, to Kelly and Fowler's interpretation.

While Kelly tells the story, Morris's forces become a kind of Greek chorus: not stilted and statuesque but almost ordinary, representing Plato's fellow-citizens of Athens, who listened to Socrates's wisdom and witnessed his death. In some way, detachment was Socrates's answer to the pressures of politics and war, and this was what Plato admired in him. So neither philosopher is represented in the dance, only the populace.

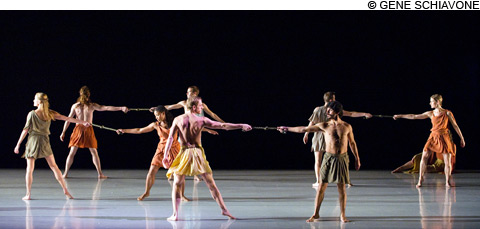

To begin ("Portrait of Socrates"), the dancers pass by in pairs, linked by short, knotted ropes. They travel in horizontal planes, adopting different step rhythms— light runs, leaps, hitch steps, gallops, bounces — and have small conversations along the way. They push and pull against the ropes, gesture to each other, declaim important words they may have heard. Nothing looks naturalistic. Everything is mirrored somewhere in the crowd. In the second section ("On the banks of the Ilissus") the pairs disperse into groups, strolling and discussing, but the formality never crumbles. Finally ("Death of Socrates") they seem to be telling each other the story in shifting groups of five, with different individuals taking the parts of the dying teacher and his mourning companions.

|

I took Socrates very much on the surface. I noted occasional poses copied from Greek sculptures or pottery, but I wasn't erudite enough to spot other Morris references to painting and literature. Not to mention other deaths, other wars, other lessons that I'm sure were there. The dance left me feeling peaceful, if not enlightened.

Opening the program were two recent Morris couple-dances. The Muir was a Scottish fantasy of the Sir Walter Scott variety, to ballads and folk songs arranged by Beethoven. Three couples, dressed by Elizabeth Kurtzman to suggest the period, sketch standard romantic-ballet tropes — watching, chasing, lifting, switching partners, rejection, despair, indecision — all in a light, speedy vocabulary laced with ballet steps. The Muir could fit right into a ballet company's repertory, but I think it would be less engaging if it weren't danced barefoot.