FLYING A new documentary follows Gerald Arpino and Robert Joffrey's enterprise through cycles of

hard-won success, financial ruin, rescue, reinvention, and virtual security, up to its present

incarnation as the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago. |

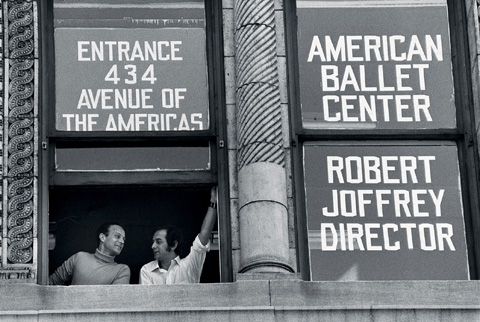

New York has two great ballet companies, New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theater. Any other ballet troupe that wants to put down roots there has to develop a personality that's distinct from those two. Essentially, this is the plot of a new documentary, Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance (it screens at the Kendall Square Cinemas at 7 pm on May 9 and comes to DVD in June).

Robert Joffrey knew he wanted to have his own ballet company from his early days in Seattle. After he hooked up with Gerald Arpino in the 1950s, they moved to New York and started a little troupe that toured on a shoestring. The new documentary follows the enterprise through cycles of hard-won success, financial ruin, rescue, reinvention, and virtual security, up to its present incarnation as the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago. The film is especially candid about some of the company's hairiest administrative transitions.

Directed by Bob Hercules, the film is largely based on the 1996 company biography by Los Angeles-based critic Sasha Anawalt, and on the reflections of Gerald Arpino, who became artistic director after Joffrey's death in 1988. It has the usual complement of dancers reminiscing about their days with the company; clips of rehearsals, performances, and classes; and a connecting narration by actor Mandy Patinkin. Dance critics Anna Kisselgoff, who covered the company in its New York years, and Hedy Weiss of the Chicago Sun-Times, and Anawalt also make appearances along with company officials and alumni.

The company history as told here is remarkably comprehensive, although it has some inevitable gaps. Robert Joffrey didn't choreograph often but the film devotes generous space to his 1967 Astarte, a sensational, multimedia duet to commissioned rock music that brought the liberated avant-garde uptown. Astarte touched off a gang of hip ballets that combined pop culture with pop music.

Arpino was really successful at this. The film doesn't fudge his reputation as a facile dancemaker who could taste the wind and make a ballet out of it. He scored big with peace-love epics like Trinity (1970), the apocalyptic The Clowns (1968), and the druggy Sacred Grove on Mt. Tamalpais (1972). Arpino could make ballet-ballets too, by the yard. His work was often vulgar and trivial, but it embossed an image of youthful daring onto the company and eventually contributed to the sexy physicality that characterizes contemporary dance now.

Bob Joffrey had exquisite taste and a sure eye for choreographic quality. Performing at New York City Center in the 1970s and '80s, the company staged a museum full of ballet classics — Petrouchka, Parade, Pulcinella, The Three-cornered Hat, The Green Table, Le Beau Danube, and more recent works by Ashton, Balanchine, Robbins, and de Mille. Joffrey commissioned young postmoderns, notably Twyla Tharp and Laura Dean, to work with ballet dancers for the first time. In those years, the Joffrey was where you went to learn ballet's history, as well as its modern spunkiness.