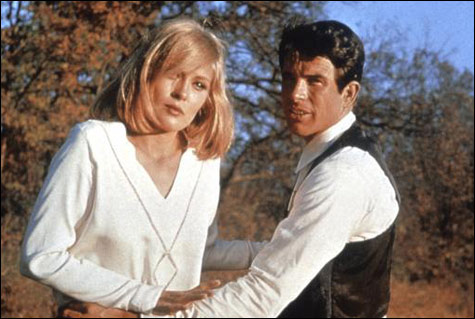

BONNIE AND CLYDE: The great American film renaissance began with this one. |

During the great American renaissance period in movies, Hollywood was in the hands of the counterculture, and filmmakers, many of them trained in the theater or under the hothouse pressures of live television, and excited by the modern classics that had come out of Europe in the ’60s, experimented with the conventions of movie genres. It all began in the fall of 1967, when Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, the first gangster picture with complex, sympathetic heroes, divided the critics (many found it morally repugnant) but made an immediate and deep connection with young audiences. They were entranced by its interplay of glamor and contemporary put-on humor, its tonal shifts, its take on the topics of celebrity and role playing, its realistic depiction of violence. Bonnie and Clyde opened the fall of my senior year of high school, and the following Monday morning it was the only thing my classmates and I could talk about. Everyone had seen it or had made plans to. My first college girlfriend told me that the weekend it opened in her town she saw it two nights in a row.

Penn flamed into the front ranks of American directors with the film’s release, so it’s easy to forget that at that point he already had a career. The fascinating Harvard Film Archive series “Arthur Penn, American Auteur” pays tribute to his early days as well as to the decade that followed BONNIE AND CLYDE (Sunday at 7 pm); it even includes one of his early television dramas, THE TEARS OF MY SISTER (Friday at 7 pm), from 1953. Penn divided his time between New York’s TV studios and the Broadway stage, and those turned out to be his entrée to Hollywood. In 1962 he brought the William Gibson play THE MIRACLE WORKER (Monday at 7 pm), which he’d directed in New York, to the screen along with its original actresses: Patty Duke as the young Helen Keller and Anne Bancroft as her teacher, Annie Sullivan. His days in TV had taught him how to harness the energy of live performance for the camera: the electric performances of the two stars make Gibson’s stripped-down dramatic text, a triumph-of-the-spirit drama about how a great teacher leads a soul locked away by blindness and deafness into consciousness, into an unforgettable emotional experience. Bancroft and Duke walked away with Oscars, and Penn had a new career.

The Miracle Worker initiated Penn’s Hollywood years and led him — through two overheated films, 1963’s THE CHASE (Friday at 7 pm) and 1965’s MICKEY ONE (Saturday at 7 pm) — to Bonnie and Clyde. (Mickey One, which marked the first time an American director had attempted to bring the sensibility of the French New Wave to these shores, is a disaster but such a bizarre one-of-a-kind picture it’s worth a look. And it has an amazing jazz score: the actors’ improvisations don’t come off half as well as Stan Getz’s.) The Miracle Worker wasn’t his first movie, though. In 1958 he directed The Left Handed Gun (Sunday at 9:15 pm), which was based on a Gore Vidal play, a Western that, in its contemporary reading of its hero, Billy the Kid, laid down a sort of blueprint for Bonnie and Clyde. With a young, camera-mesmerizing Paul Newman in the role, the film envisions Billy as a sensitive, troubled, essentially good-hearted kid, like the characters James Dean had played in East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause. (The project had been conceived for Dean.) Crude though its Freudian dramaturgy may be (and its touches of religious imagery), The Left Handed Gun is a vivifying and affecting movie, both of its time and ahead of it. Moreover, it established Penn as an actor’s director and his link to the American Method style. Newman was the first of the signal Method actors he worked with, a staggering list that includes Warren Beatty (Mickey One, Bonnie andClyde), Marlon Brando (The Chase, The Missouri Breaks), Dustin Hoffman (Little Big Man), Gene Hackman (Bonnie and Clyde, Night Moves), and Jack Nicholson (The Missouri Breaks).

The movies Penn made after Bonnie and Clyde were further efforts to grapple with the realities of living in America during and in the wake of the Vietnam War, when the old myths and genre conventions no longer seemed adequate. Some of these pictures don’t work: the 1975 film noir NIGHT MOVES (Saturday at 7 pm), with Hackman as a private eye investigating the disappearance of an LA teenager (a very young, touching Melanie Griffith), followed The Long Goodbye and Chinatown, so its treatment of rotted Southern California values felt old hat even then. (Hackman’s performance is solid, however.) THE MISSOURI BREAKS (Monday at 9 pm), from a screenplay by the novelist Thomas McGuane, is a hipster Western whose bounty-hunter antagonist (Brando) is meant to be an embodiment of the moral outrage of modern warfare, but it’s just as phony in its way as The Chase, with its besotted, bigoted Texas-small-town villains who bring pistols to their Saturday-night parties. What The Missouri Breaks does have is one of those jaw-dropping wild-card displays from Brando that no one who admires his work can afford to miss. Nicholson’s beautifully calibrated performance, which operates as a springboard for Brando’s glorious excesses, is a reminder of how controlled an actor he once was. And though it has some very funny episodes in the first half, Penn’s 1970 adaptation of the Thomas Berger novel LITTLE BIG MAN (Saturday at 3 pm), framed as the tall-tale reminiscence of a 121-year-old survivor (Hoffman) of Custer’s Last Stand, is so baldly ideological, with its Asian-looking Indians slaughtered en masse by a sociopathic Custer (Richard Mulligan), that, seen out of its era, it’s almost incomprehensible.