A job at Cerrejón is a good job by Colombian standards. Although the pay is far less than a comparable job would pay in the United States, but workers enjoy a strong union, health and education benefits, and pensions. Subcontracted workers are generally not so well-off. They aren’t covered by the union contract, and their jobs are lower-paid and often temporary. Still, a job is a job, and, in a country with a poverty rate of 50 percent and unemployment ranging from 10 to 20 percent in recent years, a job is not to be sneezed at.

The company’s profits flow around the world. Coal is now Colombia’s second largest legal export, following oil, and Cerrejón’s exports represent an important source of foreign exchange for Colombia. The company pays royalties of more than $100 million US dollars a year to the Colombian government, much of which is returned to local municipalities.

The profits also flow into the coffers of the three multinationals that own the mine, benefiting their employees and executives. And Cerrejón pays out more than half a billion dollars to its shareholders every year. In 2005 it reported close to $450 million in retained profits. The communities affected by the mine got a much smaller compensation from the company’s operation: Cerrejón spent just $2 million in its “communities division.”

Even that relatively paltry sum never seems to make it to the people for whom it is earmarked, complain the residents. Most of the money, they say, ends up in the hands of corrupt officials. Cerrejón admits that its royalty payments often fail to reach their prescribed destinations, and in July 2006 implemented an oversight commission to monitor its distribution. The commission has not issued any public report.

The company has also, obliquely, admitted that its comportment in the displacement of Tabaco was unacceptable. “We realize that mistakes were made in the case of Tabaco,” said Cerrejón president León Teicher. In Cerrejón’s 2006 Sustainability Report, the company explained that one of its corporate goals is to “prevent the displacement of individuals, groups and communities.” These words ring a bit hollow to Tabaco’s former residents.

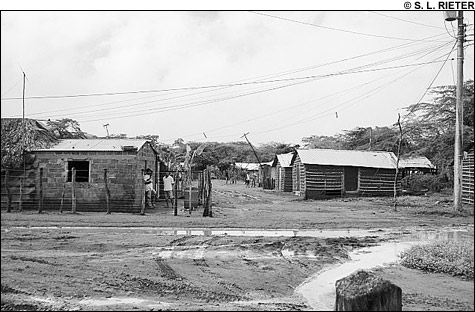

LAND OF THE LOST: These photos show the impoverished villages that abut the Cerrejón mine, including Chancleta.

|

Safety hazards

In a country notorious for having the highest levels of both government and paramilitary violence, in which trade unionists, journalists, and human-rights activists are often targeted, Estivenson Ávila is a man with a particularly dangerous job. He is the president of the union of workers at the Drummond Company’s La Loma mine, Colombia’s other giant multinational coal pit, which supplies a sizable proportion of the fuel burned in Massachusetts power plants. His two predecessors, Valmore Locarno and Gustavo Soler, were both assassinated by paramilitary forces, pulled off a company bus on their way out of the mine at the end of their shifts. Their families have accused Drummond officials of being behind the murders. Several former paramilitary leaders, now in prison, have testified that they saw the president of the La Loma mine meet with and give money to paramilitary commanders in the region. Drummond categorically denies the charge, though it acknowledges that the right-wing paramilitaries operate openly in the area and that they were responsible for the murders.

The victim’s families have brought their case before a US court, with the help of the United Steelworkers and the International Labor Rights Fund. An Alabama jury voted in July that there was insufficient evidence to prove that Drummond was behind the killings. The plaintiffs plan to appeal, arguing that the judge disallowed two of their most important witnesses. Upon hearing the verdict, Ávila commented: “The value of my life has just dropped dramatically. If the company gets away with killing Locarno and Soler, why not just get rid of me, too?”

Working conditions at Drummond’s La Loma mine are significantly worse than at Cerrejón. Wages are lower, and health and safety conditions poorer. Workers complain that Drummond’s vaunted “efficiency” tactics severely compromise their health. At a meeting with an international delegation this past summer, union workers explained that Drummond’s system of extracting huge boulders uses a conveyor belt–apron feeder system to drop them into trucks, where the drivers are repeatedly jolted and shaken by the impact. Severe spinal-cord injuries are common. According to the union, more than 150 truck drivers have been injured in this manner, 15 of whom have been permanently disabled.

“The company won’t let us see a doctor until our seven-day shift is over,” one worker complains. “Then the company doctor always says there is nothing wrong and makes us go back to work.” In addition, workers say they’re afraid to report injuries, because the company will simply fire them.

Communities in the vicinity of the Drummond mine face the same poverty, displacement, and environmental contamination as those near Cerrejón. In the town of La Loma, where most workers retreat to sleep after their 12-hour shifts, they frequently find that there is no water or electricity.